Mar 15 2015

2015 AERC Convention

"Subscribe to Endurance Riding!"

The boys and I enjoyed our quick trip to Reno for the AERC Convention over the first weekend in March. The highlights for the boys were, of course, go-kart racing, laser tag, and video games galore in the hotel’s arcade. I, on the other hand, enjoyed attending two different seminars on Friday. The first one was on 100-mile horses and what makes them successful in the longer distances. Several horses were surveyed at various 100-mile rides. Here’s what was discovered:

- The biggest cause, representing 55% of the pulls, was lameness (front limb lameness was more common than hind limb lameness)

- Rider Option was the second biggest cause of non-completions in the 100-mile rides

- Lameness pulls (and this isn’t a surprise) were 8 times more likely if the horse required corrective shoeing

- Training more days per week increased the probability of both lameness and metabolic pulls (take home message: Do Not Overtrain!)

- Cross Training and Fat Supplementation largely DECREASED the risk for lameness pulls

- Interestingly enough, a 4 year study conducted overseas showed no relationship between speed and lameness elimination

- While feeding grain and beet pulp the morning of a ride (which, after attending an equine nutrition seminar a few years back, I stopped doing) decreased pulls, it is beneficial to decrease grain in the off-season.

- Here’s a no-brainer (although not always feasible): Trailering for a shorter amount of time (i.e., attending closer rides) decreased the chances of lameness pulls

- Competing in the fall, after Spring competition, increased chances of a pull (in other words, the longer the competition season, the harder it was on the horse – REST is important!)

Lameness pulls are more often than not associated with higher heart rates and poor overall impressions. Lameness pulls usually occur later in the ride (averaging around mile 70) versus metabolic pulls (metabolic pulls often occurred around mile 48). The second seminar I attended was titled “Gastric Ulcers in the Endurance Horse.” For those of you who do not know, I discovered a few months ago that my schooling horse, Forest, an 11-year-old Appaloosa, has Grade 4 gastric ulcers. He is not an endurance horse; he has the least stressful life of my entire herd, so we’ve (meaning my personal vet, the vet team at UC Davis, and myself) have been unable to ascertain why he has ulcers, but we have been able to successfully treat him. I was particularly interested in this seminar to see what the recommendations are for managing a horse with ulcers. Here are my cliff notes on the subject; taken from my several pages of notes:

- Vague signs of ulcers in the equine include (but are not limited to):

-

- Dull hair coat

- Picky eating

- Lying around

- Sour attitude

- Being “cinchy”

- Poor performance (reluctance to train)

-

- Unfortunately, some horses with ulcers show no clinical signs whatsoever, BUT after treatment, show improved performance.

- Clinical signs increase with the intensity of exercise.

- The more severe the ulcers, the more likely it is for the horse to show signs.

- The only definitive diagnosis is through GASTROSCOPY.

- Why do horses get ulcers?

-

- Small stomach

- Constant acid secretions

- Manmade conditions

-

- Risk Factors:

-

- Intense exercise

- Extensive hauling

- Changing environments/routines

- Limited turnout/grazing

- Stall confinement

- Diet: high grain, low forage/roughage

- Poor teeth

- NSAIDS (giving Bute/Banamine too regularly)

- Hypertonic oral electrolytes (a catch 22 for endurance riders!)

-

There are two kinds of ulcers: Squamous ulcers and Glandular ulcers, and these ulcers are rated from 1 (Reddened or thickened areas, but no actual ulcers; think pre-ulcers) to 4 (Extensive, deep ulcers). The glandular region of the stomach is a very susceptible area to ulcers, and unfortunately, ulcers in this area are difficult to treat and require a much longer treatment cycle. How common are ulcers???

- It is estimated that 75-95% of Thoroughbred racing horses have ulcers!

- 60-70% of endurance horses have gastric ulcers. Because of the aerobic exercise endurance horses experience (which increases gastric acid, and the motion of movement which splashes this acid around, coupled with decreased blood flow to the gut during exercise — similar to marathon runners; they experience ulcers too), they are susceptible to gastric ulcers.

- It is believed that 36-48% of Thoroughbred racing horses have Grade 3-4 ulcers.

- Ulcers are so prevalent in horses that Grade 1 (those reddened, thickened areas) is now considered normal in all horses.

SO, what do we do about these ulcers???

- Treat with a full dose cycle of GASTROGARD (omeprazole) for a minimum of 28 days.

- Sucralfate can help coat the stomach and decrease pain.

- Include some alfalfa in your horse’s diet (alfalfa contains calcium, magnesium, and protein — all which work as buffers)

- Give free choice hay using slow grazer feeders (grass hay is best — this is closest to mother nature; grain hay has too much starch)

- Eliminate large amounts of grain and simple carbohydrates from the diet

- Feed a small roughage meal 30 minutes prior to exercise to act as a buffer and reduce the splashing of gastric acid

Horses should not live on omeprazole every day, so following the initial 28-day treatment, re-scoping is recommended (to see if the ulcers have healed). A preventative dose of omeprazole can be given before competition or a known stressor by treating with low-dose omeprazole 5 days before the stressor and continuing seven days afterwards. Good news: Horses can, sometimes, self-heal ulcers with:

-

-

- Time off

- Grass

- Turn out

-

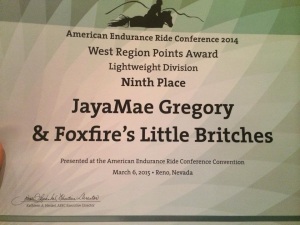

It was an educational and fun weekend! Of course, the ultimate highlight of the weekend for Jakob and me was receiving our Regional Awards: